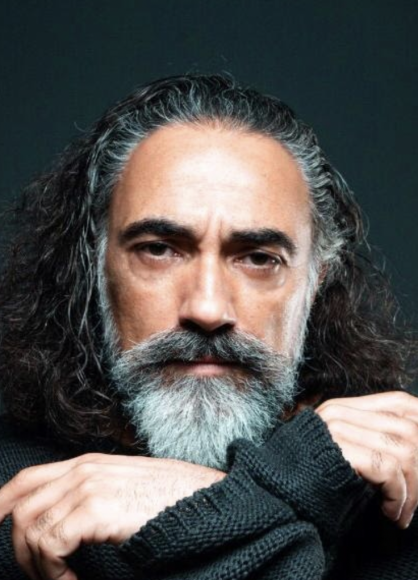

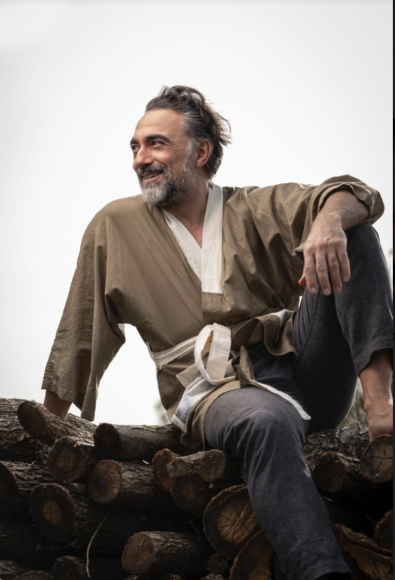

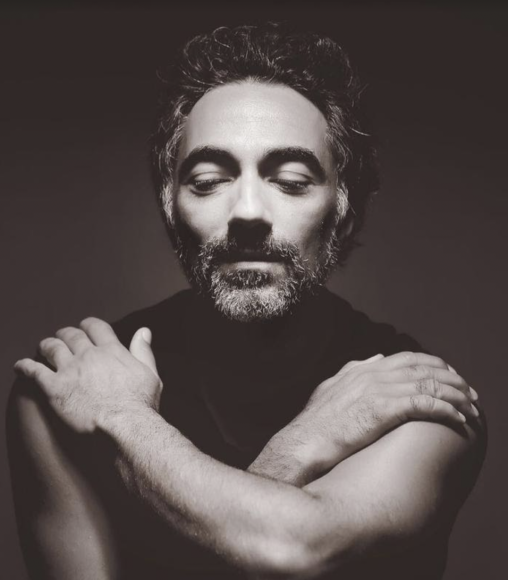

The famous Turkish actor Selim Bayraktar was born in Kirkuk, Iraq in 1975, from a Turkish father and Turkman mother. Due to the unrest between Iran and Iraq his family migrated to Turkey which is where he became interested in theatre as an actor. As the years went by he shifted into TV and found his career blossom in 2006, following his portrayal of the role of Sumbul Agha in Suleiman The Magnificent Century (Muhtesem Yuzyil) a Turkish historical fiction television series broadcast worldwide. The Magnificent Century is one of the most successful Turkish dramas; a historical series of the Ottoman empire, that has been dubbed the “Turkish Tudors” and aired in almost 70 countries spearheading an international boom for Turkish drama. Following this, he received international recognition with his role in the Netflix original series Rise of Empires: Ottoman.

Selim Bayraktar is very rarely gives Interviews and prefers keeping a low profile personally and professionally adding to the man’s mystique. We got the exclusive opportunity to uncover his views on fame and the spiritual connection he has crafted with audiences far and wide.

What’s the most challenging thing about bringing a script to life?

You start with the script, of course, and with any admonitions the director may have to give you. The actor is a kind of shaman. And If the audience is lucky, we go through this emotional magic to other worlds and other versions of ourselves. Our enchantment or immersion into another world is not just theoretical, but sensory and emotional.

How do actors and audiences achieve this shared mysterious transportation?

This shared ritual draws upon a kind of sixth sense, the imagination. The actor’s imagination has gone into emotional territories of intense feeling before audiences so we guide them like a psychopomp into those emotional territories by recreating them in front of them

The entertainment industry is said to be full of stress and pressure, how has success changed your life?

It’s so hard to deal with… We don’t always feel comfortable admitting it to our friends; it is embarrassing. But, secretly, the idea of being famous has great appeal. Fame is deeply attractive because it seems to offer very significant benefits. The fantasies go like this: when you are famous, wherever you go, your good reputation will precede you. People will think well of you, because your merits have been impressively explained in advance. You get warm smiles from admiring strangers. You won’t need to make your own case laboriously on each occasion. When you are famous, you will be safe from rejection. You won’t have to win over every new person. Fame will mean other people will be flattered and delighted even if you are only slightly interested in them. They will be amazed to see you in the flesh. They’ll ask to take a photo with you. They’ll sometimes laugh nervously with excitement. Furthermore, no one will be able to afford to upset you. When you’re not pleased with something, it will become a big problem for others. If you say your hotel room isn’t up to scratch, the management will panic. Your complaints will be taken very seriously. Your happiness will become the focus of everyone’s efforts. You will make or break other people’s reputations. You’ll be the boss.

What is your mantra of success?

The goal is not the destination. The goal is the way you get there.

Have you ever thought of acting in Saudi Arabia?

If there is an offer, why not? على رأسي ((:

How do you feel when you make your fans engrossed in the lives of your characters?

Acting (like other collective artistic work) can be a kind of mainlining of intimacy, and the fans partake of this intimacy too. There’s a lot of subtle embodied communication going on and there’s an intense awareness between the fans and actors.

When art is good – when the acting and the script are on point, the fans actually learn more about human behaviour than real-life observation provides. This is because the interior of the character is articulated in art, whereas it remains submerged in real social interaction.

Text by Suna Ahmed